On Friday 14 September 2012, Vanessa Gardiner gave the following talk at Sladers Yard:

In April 2008, I visited Greece for the first time – it was only for five days to Athens – but it seemed both necessary and urgent for me to follow a newly discovered architectural direction in my work and to see the Parthenon with its embodiment of pure architecture, perfect proportions, order and clarity. Not only did the complete beauty of the Acropolis exceed all my expectations, but I was very excited by the city of Athens itself and the landscape of the Attica coast. In the summer of the same year, I returned, this time to the Peloponnese, and visited the ancient sites of Tiryns, Mycenae and Epidauros, whilst based in the town of Nafplion.

It was intriguing to see the unified, architectural ruins of the citadel at Mycenae in relation to my earlier visit to the Acropolis in Athens; how its structural arrangement seemed to follow the natural lines of the surrounding hills. I did a series of drawings, both from there and from other landscapes I visited in the Peloponnese, but felt that there was much more to pursue and that it would be necessary to return if I was to develop these ideas into paintings.

With this in mind, I applied to the British School at Athens for the Prince of Wales Bursary for the Arts and I was delighted to be awarded the grant, which enabled me in April 2009 to embark on a series of trips to Greece. It proved to be an immensely rewarding and productive year, enriching my work profoundly and resulting in a large number of drawings and watercolours, many of which I have used as source material for the paintings in this exhibition.

I made a decision from the start of the Bursary to make several separate visits to Greece. This fitted in with the process of how I work: returning repeatedly to specific places of interest to glean more information to use in the paintings back in the studio.

I am pleased I decided to spend the time in this way, as it has meant that I have had the chance to travel around some of the country and in doing so I have seen both the different aspects between places as well as the surprising similarities which the landscapes can reveal.

I have had the benefit of returning to the same places at different times of year – so seeing say Mycenae in the dry, arid heat of late August and then looking remarkably green in early December; the citadel, which appears in summer to be so harmoniously placed within the landscape, seemed quite stark and fortress-like against the dark hills in December. I also became acutely aware of the significance of the sea and the way it connects the country together and in a sense is as much a positive as the land itself.

Staying first in Athens at the British School in April, where apart from drawing from the south slopes of the Acropolis and the Pnyx, I re-visited Sounion on the Attica peninsula as well as visiting the Saronic island of Aegina. Here the beautifully-sited temple of Aphaia is intriguingly part of a perfect equilateral triangle with the temple of Poseidon on Sounion and the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens.

Later that year I returned to the Peloponnese and based myself back in the town of Nafplion, which has resulted in a number of paintings inspired by the Argolid coast.

From here, I made trips out to the many ancient sites nearby, including Mycenae and Tiryns and then carried on down to the Cycladic island of Paros – initially to fulfil a long-standing wish to see Delos, which I did, but I also became unexpectedly attached to Paros, and the inland village of Lefkes in particular.

In March 2010 I held an exhibition in Athens, at the British School, of all the drawings and watercolours I had done accompanying this with a short talk and last year I showed paintings at the Hart Gallery in London. I have since made a number of visits back both to Athens and Nafplion to continue my work.

Although my paintings have long been inspired by the highly structured coastal landscapes of Cornwall and Ireland, I had for some time believed that there may be connecting aspects which corresponded in some way to the clarity and precision found in the Greek landscape.

I have, over the years, become increasingly fascinated by the visual language I use in my work to evoke landscape and by the geometry of actual architecture – both ancient and modern. Some years ago, the influence of drawing from the simple lines of the Cistercian monastery of Le Thoronet in Provence was crystallised by the experience of seeing the monumental temples in Egypt in 2004.

I was immediately struck by the austere simplicity of the architectural ruins I saw there and the abstract shapes emphasised by the intense blue sky between the columns of the temples. I felt that there was in a sense a parallel between my landscape forms and the architecture of the ancient monuments and this inspired a number of paintings.

The harmonious beauty of the classical Greek art and architecture and its relationship within the landscape seemed to be a natural progression and during that first visit to Greece sitting on the bus from Athens to Sounion, I was struck by the apparent similarities with the linearity of the Attica coastline and that of the Cornish coast – which is so familiar to me.

I am always inspired by new landscapes; they help to drive my work forward and so entering this new but connecting subject matter of the Greek landscape was very exciting. I wanted to use the opportunity to draw as much as I could, knowing that it might not all be of immediate use, but that I could refer back to it sometime in the future. Equally, I was very much aware of not overloading my visual senses with too much subject matter to then consolidate into paintings. My initial thoughts were how I could depict the places and still remain true to them in my paintings.

The ancient site of Sounion is on the tip of the Attica peninsula on the mainland. It is an evocative place as are so many of the ancient Greek sites and it is one of astonishing beauty. Here, the Doric temple dedicated to Poseidon resides, strategically perched high on the edge of the cliff looking across the Aegean towards the Cycladic islands.

The experience of seeing this panoramic landscape for the first time was profound and I remember consciously thinking then that there was so much that I would like to do with such a beautiful place.

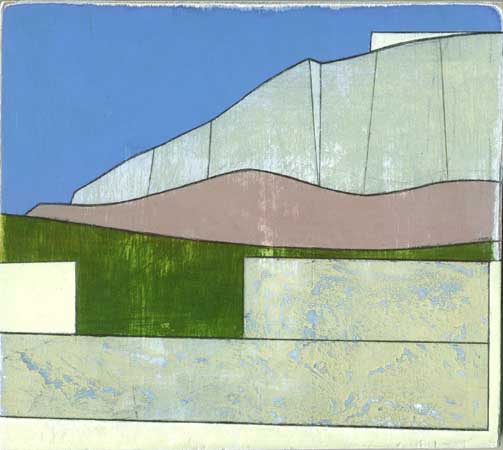

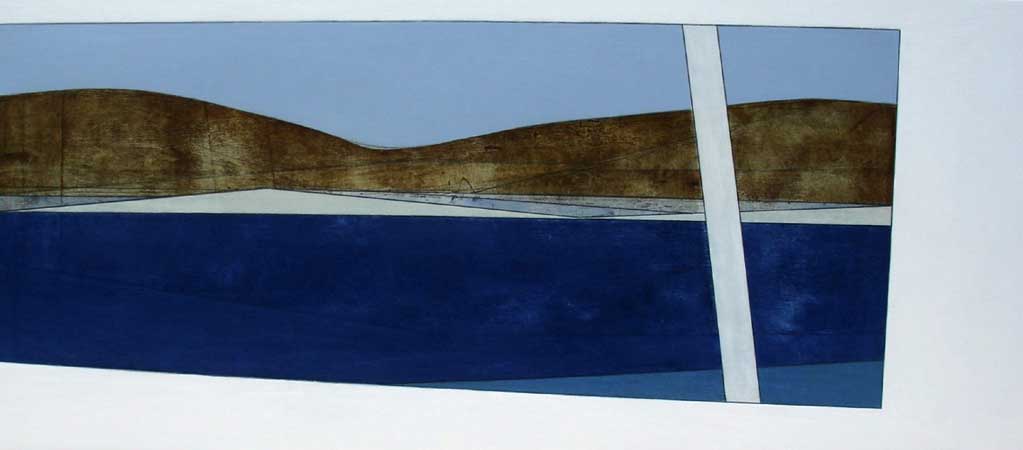

The sea is often an intense cobalt blue, which can have an unexpected opacity about it, appearing at times to seemingly float as a solid band of dense colour across and between the headlands. Because of its proximity to the Cyclades, the light on the Attica promontory is often particularly crystalline. It is a clear, sharp light, which enhances the purity of the lines and contours of the pale grey hills, studded and mottled by scrub. The broken lines of paths and roads as they traverse the hills appear to swing across the contours of the land, revealing the differences between Greece and other landscapes I’ve worked from. I recognised all these elements as parallels to the visual language I use in my paintings.

I have since made over fifteen trips to Sounion, picking up the bus in Athens and making the two-hour journey along the Attica coast for a day’s drawing. It seems to me that this one place somehow encapsulates the whole of that expansive Aegean landscape.

In the series of paintings I’ve made from the site, I have tried to depict the rhythmic qualities. The white fragments of ancient pillars and marble in the foreground, lying in harmony with the shapes of the headlands beyond. The elements becoming almost interchangeable set against the deep cobalt of the sea.

I find it essential to get to know a place well before beginning to paint from it and couldn’t envisage starting paintings from landscapes without the initial process of drawing. I can in some sense then feel justified in abstracting and re-ordering the landscapes into the carefully selected compositions I use later in the paintings.

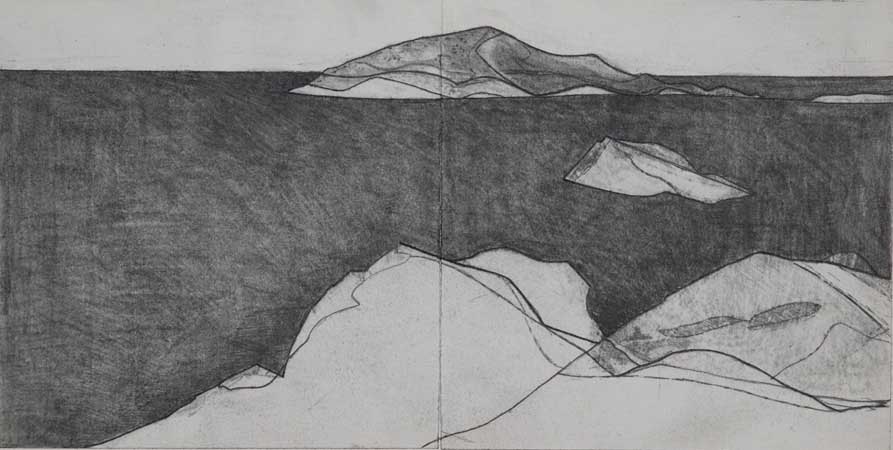

I always take a sketchbook with me and will make many drawings directly from the subject. I tend to use small books as they are more practical to hold standing up and are useful for both quick, urgent sketches as well as for longer, more detailed, observational drawings. Often I draw across two pages and sometimes, if I find the landscape I am working from is larger or longer than the space I have to use, I have a mechanism for folding the pages over and working on the next sheets thereby being able to continue the drawing that way.

Some of these may be close, observational drawings made over a period of time or quicker notes made purely to glean some specific information.

In my experience with drawing, what you actually see is invariably more interesting than anything which could have been invented. It is through drawing that you start to truly look and imprint and interiorise a lasting image in your mind. It is then that you might notice all the idiosyncrasies that characterise the Greek landscape – the singular, pure line of the hills, the sharp quality of the sea when it abuts against the coast and the co-existence within the landscape of an elegant linearity with strong geometrical forms.

I came across a note I had made to myself in one of my sketchbooks about drawing:

Don’t short-circuit by not drawing first – it is the drawing which gives the information and the inspiration for the painting. (You can’t expect to get there too quickly). The ideas come through drawing and the experience of drawing and the time taken – the one feeds the other. The ordering and reflection which takes place later is often decided by the initial drawings.

On one occasion I spent all day drawing the headlands at Sounion but it was only while waiting for the bus back to Athens that I made a quickly executed small sketch which I knew had all the information I would need to translate into the formal composition for a painting. Equally, however, I doubt I would have arrived at such a focused result without having spent the day drawing.

Another point I value about using sketchbooks and making drawings directly from the subject matter is exactly that: they were made there and then in front of the place and are an immediate reminder and very real recollection of that place – the drawings recall it instantly and there is a kind of warmth about looking at them again back in the studio and remembering the time I was there, drawing – sitting at the edge of the promontory.

I use drawing fundamentally, therefore, as a tool for exploring new shapes and directions to use in my paintings knowing that these will be true to the place.

One of the reasons I decided to use watercolours was that by coming to Greece and painting from a new subject matter and a new colour palette, I thought it might be a good opportunity to do some work in a slightly different way from usual. I hadn’t used watercolours for over 20 years and thought that their compact and transportable qualities would be appropriate for taking with me.

In fact, they have proved an excellent medium for such a hot climate: they dry quickly and have a freshness, vitality and spontaneity, which is good for attempting to capture the particular light of Greece. There is an immediacy about watercolour that is both enjoyable and rewarding. I tend to use them alongside pencil, re-drawing over the paint while it dries. A similar process, therefore, to solely drawing directly from the subject matter, but less controlled and ordered and essentially providing me with the vital colour notes I need.

Although I take some photographs, I rarely use them – they act instead as a kind of insurance policy for me; I can continue drawing from the subject knowing that I do have the photographic information, if ever needed.

All of this then feeds into my paintings back in the studio. Certain drawings and watercolours will go onto the wall and I’ll start to select those elements I feel will best evoke the landscape – a distillation, in a sense, of the lines, shapes and colours.

However, to find a way of consolidating all that I have accumulated and to start to translate it into paintings is a formidable task!

For it is now a matter of fixing down the experiences and images from the directly observational drawings. Paring them down to the essential elements found within the landscapes and yet remaining true to the place and retaining something of the freshness of the observed work.

It takes time for the initial ideas to truly mesh and instil themselves so that I can start to compose the paintings. The design is very important to me and it is only by working on the picture that this truly evolves. I am very aware of not wanting to make a purely descriptive view and so by selecting qualities in the landscape which emphasise my particular interest, I find the painting can become closer to an evocation of the place, rather than a description. It is often what you choose to leave out which can be as important as the elements you decide to put in.

When returning to a landscape in Greece, I am also thinking of the paintings I am working on back in the studio at home. Over time, it can become hard to recall all that I want to work on and this can leave me with a sense of being out of touch. I return partly to be reminded of what it is that I want to work with and to feel justified that what I am doing with the paintings in the studio is true. So I will travel back to glean more information, make more colour notes or draw further views to enhance and refresh my ideas.

There is often a delight in returning to the sites: there they are again, those familiar shapes and colours, all in the pictures back in the studio and at times it feels almost as though I am walking into one the paintings themselves. Sometimes I am surprised to recognise a certain shape and to be reminded about how I arrived at it – it is both reassuring and encouraging to see the sources for the shapes I have used and that they do really exist and to rediscover them when drawing from the subject.

And, in a sense, the way in which I have repeatedly returned to these same locations over the course of the last four years, parallels that of my process of dipping in and out of my paintings and their subject matter. Part of painting the picture then becomes this physical journeying back-and-to to these landscapes; taking the trips back to the actual sites over the years and returning to them in the paintings and reworking those over the months (or even years).

I find it amazing how clearly a particular landscape can be recalled to memory. There have been times when my studio has almost resembled being in Greece to me. Entering it with the intimacy of those well-known places: the paintings and drawings and colour notes on the walls and pieces of rock to remind me of the colours on my shelf.

Although it can be quite difficult, of course, in the depths of winter and working in a cold studio to rekindle the sensations of the hot, dry Greek landscape of 40 degrees.

But this is also where certain detachments are interesting: for it is this distance, both physical and mental, which forces one to attempt to create a sense of the place by means of semi-abstracting from all the experiences of being there. When drawing directly from landscape, I am inundated with visual material in front of me and although the selection process to some extent starts then, it is by having this physical distance from the subject as well as the more reflective time in my studio, that I can start to truly select and consolidate my ideas into paintings.

What interests me is the transition from the closely observed drawings made from the haphazard, natural landscape to the order and precision arrived at in the composition. This transition moves the subject into another sphere and becomes something else in its own right, despite being still rooted in the observed world.

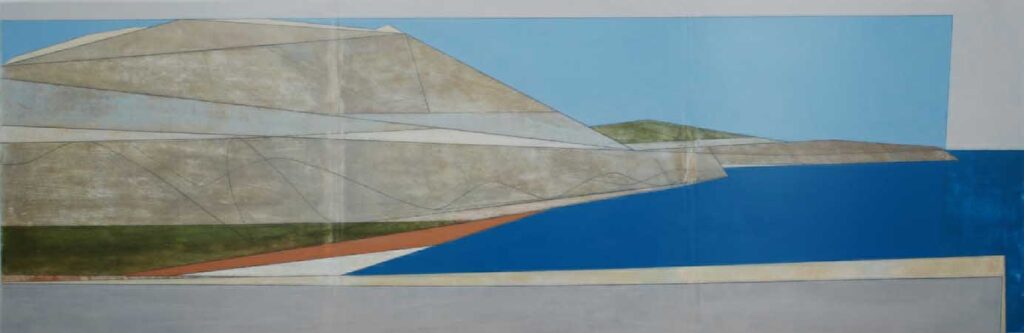

The painting technique I use of scouring and sanding back the paint surfaces becomes in a sense the equivalent to the more random disorder found in the natural landscape.

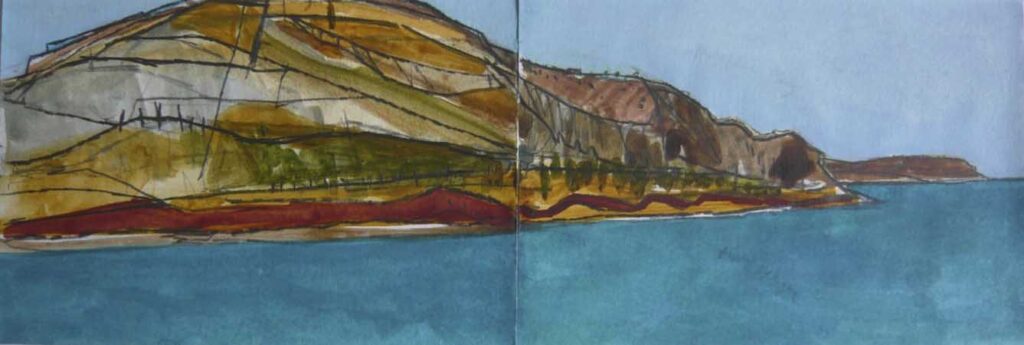

In the Peloponnese, two singular landscapes have been particularly inspirational: the austere, long headland which juts out into the Argolic gulf at Nafplion and, on the same stretch of coast, the dramatic Fortress of the Palamidi which stands vertiginously on the summit of a rocky cliff commanding a view of the whole of the bay.

I have made many drawings of this panoramic line of coast and a series of paintings have followed. Here the sea is a palpable turquoise and very different to the cobalt blue on the Attica coast as it forms a sharp line against the mottled grey peninsular. There is a distinct wildness here – an untamed quality about the landscape.

The large painting I’ve called Argolis Wall is a direct translation from a small drawing I’d made over four pages – the landscape being far too long a format for the sketchbook I was using. I initially began this painting on four hardboard panels, with the intention of replicating the four sketchbook pages. But over time, while working on the piece, I reduced the panels to just three and eventually decided on unifying the whole picture together as one by fixing the panels onto another board – the unexpected direction of the painting process!

The lofty, precipitous fortress of the Palamidi is accessible by climbing up nearly 1000 steps and I’m sure this exhausting but exhilarating ascent, often taken in the blazing heat of summer, enhances my perceptions whilst drawing up there, perched high above the Argolic Gulf. Here the architecture of the steep walls of the building seem almost to merge with the natural architecture of the pale grey rocky cliffs as they plunge down to a turquoise sea. The composition lends itself to the vertical, which is an unusual format for me.

On the boat to the Cyclades, the white rigging looked stark against the indigo-dark sea, and here I was conscious of entering a different kind of Greece where the light was dazzling and the colours on the islands of Paros and Delos were of ochres and rich umbers. I was aware of how the lines of the landscape seemed to lengthen and flow and the straight vertical pillars and the marble entablatures on Delos appeared to parallel that of the sea’s horizon.

When referring back to a sketchbook I had used on Delos, I noticed a list I had jotted down, next to a drawing, which read:

White light,

Rhythms of slopes,

Walls,

Very dark water,

Vertical white pillars,

Granite and marble,

Mustard coloured wild areas,

Very windy,

Lizards,

White crests to indigo, dark sea,

Pale mauve sky,

Amazing light,

Mystery.

A series of paintings of Delos have followed. In the large painting of Delos 7, I wanted to express the great strength of the Doric columns as they both pull down towards the ground as well as to create a feeling of soaring upwards.

I like the sense of the pillars becoming flat, opaque shapes against the fluidity of the landscape.

I have tried to find equivalents to the actual marble slabs and entablatures with the paint. It is almost by accident, however, that the methods by which I work have arrived at this physical resemblance to stone. The effect of the many stages of continuous sanding, scouring, re-painting and varnishing is one of weathering in the same manner as stone does when exposed to the elements.

The painting technique I have developed over the years is a crucial part of my work and it involves a continuous series of procedures: I begin a painting by laying out the image based on the information from the sketchbooks onto a well-primed board, organising the shapes and forms of the subject matter both with paint and by drawing.

Next I embark on a series of processes, invariably involving painting, sanding back or scouring off some of the paint, redrawing the image and repainting it. I am constantly alert to the unexpected results that this might uncover and follow these leads in a conscious way. At times, I might completely obliterate the picture with white gesso, let it dry and then scour off the white to reveal the image beneath. I then continue with the painting, to some extent following its previous history.

All this leads to the paint surface being significantly changed and enlivened and the board taking on a beautiful patina – a burnished surface almost – revealing qualities of its own.

I might work on a series of six of seven paintings at a time, rotating them in the studio as I go, so that ideas from one will feed into others, having the effect of unifying them together.

I paint on either plywood or hardboard as they are robust and because, if necessary, I can cut them and resize them and not therefore restrict the work to a prescribed format. They also respond beautifully to all the sanding and weathering during the painting process, leaving traces and histories of the paint and incised lines in their grain. I work with acrylic as it dries quickly and lends itself well to my technique.

I am aware of not wanting to fix an image down at too early a stage in the course of a painting and to keep some kind of fluidity – which the Greek landscape has – and sensing at one point that the painting of Delos had become too static, I completely whitened it over with gesso.

This action has a slightly transparent effect and I find that I can draw over the painting underneath with a very sharp pencil while the gesso is still wet. When the painting is dry, I will sand it with fine-graded sandpaper and then wipe it over with a cellulose sponge and add medium to this to enhance and secure the surface. I then re-incise the lines with the pencil. By this time, the graphite becomes very black and the pencil crunches through the brittle, white ground.

The process has the effect of re-invigorating the painting and I can now select and emphasise certain lines and shapes within the composition as a whole.

The result becomes a new surface but retains the history of the past picture underneath. They are not lost – all those hours I’ve worked on it – but re-used instead. It can feel like a huge risk however, and at the start I find myself taking a deep breath before embarking on covering it over with the white paint! Invariably the traces of the previous painting underneath are useful and often help to direct the picture forwards. The lines now delineate and hold in the scratched and scoured areas. It is then a matter of carefully re-painting the shapes. I am by now crucially aware of what to select within the painting and there becomes a dialogue between the transparencies and opacities, the lines and the shapes.

Painting the edges of the picture white is an integral part of the process and is usually a final but important stage. I always do this as I find it in some way helps to pull the painting together and in a sense to hold it in.

It is this physical engagement with the materials, together with the rational ordering of the image in my mind and the unexpected results that may occur, which I find so enthralling: the linearity of the graphite with the rubbing and scraping of the paint surface so that the many different applications of the paint coalesce; and by repeatedly washing and scrubbing the plywood and responding intuitively to the traces and after-images which are left at each stage, I hope that something beyond the subject matter and the material will emerge, some otherness, as it were. I find that it is only by constantly working every day that I can be truly alert to those moments when something might appear which will be a crucial element in the picture.

The whole experience of working from Greece and dividing my time between visiting the landscapes over there and working on the paintings here at home has been immensely rewarding and valuable to me and I see it very much as an ongoing project and not something that has a definitive end but one which will continue to sustain me for years to come.

In April this year I went back to Greece, revisiting the island of Aegina and then on to Ancient Corinth for the first time. Both enriched me with ideas for future paintings. At Corinth, I was struck by the sheer bulk and simple lines of the austerely beautiful Doric Temple of Apollo.

Later that same month, I also returned to the north Cornish coast and back to Boscastle, where walking the cliff path vividly recalled to my mind the rocky promontory at Sounion.

It’s reassuring, therefore, that my initial ideas about those connecting aspects between both the landscapes and my paintings of Cornwall and Greece are indeed validated. In some respects then, perhaps I have come full-circle and it could now be interesting to see how the influence of working from Greece might filter into some new paintings of Cornwall.

©Vanessa Gardiner 2012

Sladers Yard

West Bay Road

West Bay, Bridport

Dorset DT6 4EL

gallery@sladersyard.co.uk

Tel. 01308 459511

© Sladers Yard 2024

Café Sladers

Licensed Restaurant

Events

Information

Weddings and Parties

café@sladersyard.co.uk

Site by FER

Sladers Yard

West Bay Road

West Bay, Bridport

Dorset DT6 4EL

gallery@sladersyard.co.uk

Tel. 01308 459511

Café Sladers

Licensed Restaurant

Events

Information

Weddings and Parties

café@sladersyard.co.uk

© Sladers Yard 2024. Site by FER.